In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

If I were to say to you, ‘The Blue Pill’ I suspect you would think of Viagra®. There is another blue pill though. If I asked that same question in the 19th Century, the answer would be mercury.

Mercury is also called quicksilver as it is the only metal which is liquid at room temperature and pressure. It was also known as hydragyrum, hence its elemental symbol is Hg. Mercury has been extensively used in medicine, most famously as a treatment for syphilis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Apothecary’s jar c.1750 for Pilulae Mercuriales.

Reproduced with permission from The Thackray Medical Museum, Leeds.

The blue pill was made of mercury chloride, also known as calomel, mixed with liquorice root, and depending on the recipe, marshmallow or confection of roses. The use of mercury as a treatment for syphilis is based on the classical teaching that it was good for skin diseases and it was soon adopted in the 1490s as the syphilis epidemic spread across Europe.

It was advocated by Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493-1541), also known as Paracelsus, a Swiss doctor and alchemist during the Renaissance. He was a fascinating figure, rejecting the accepted dogma of Hippocrates and Galen, he supported experimental medicine (“The patients are your textbook, the sickbed is your study”) and as a chemist (or alchemist) proposed the use of minerals or inorganic substances as drugs. He was very clear that the amount of medicine was vital stating, “Sola dosis facit venenum” meaning that it is the dose of a substance that determines the difference between medicine and poison; the basis of all pharmacology! Equally however, he rejected the four humours of Hippocrates replacing them with his own three, salt, sulphur and mercury, and as an astrologist he taught that diseases were caused by poisons sent from the stars. He also believed in four elemental beings: Salamanders (Fire), Gnomes (Earth), Undines (Water) and Sylphs (Air).

Mercury, as Paracelsus correctly pointed out, is poisonous particularly in large doses. One reason it was used to treat syphilis was the diuresis and excess salivation it caused – this was felt to wash out the poison. The more salivation, the better the cure, so unfortunately, patients were given large doses. Excretion of at least three pints of saliva a day was felt to indicate a good result.

Many patients suffering from syphilis were poisoned with mercury, their gums bled, their bowels were ulcerated and their teeth fell out. This miserable existence, suffering not only the ravages of their sexually transmitted disease but also the poison of its ‘cure’, led to the rather dry witted rhyme, “A night with Venus; a lifetime with Mercury”.

Ulrich von Hutton (1488-1523), a contemporary of Paracelsus, took mercury for his syphilis. After all his teeth fell out, he wrote violently against its medicinal use preferring instead Guaic Wood: the striped heartwood of the Palo Santo tree of South America, also known as Holy Wood or the Tree of Life. Based on the theory that where a disease was found, God ensured a herbal cure grew in the vicinity, it was felt a likely cure for a disease imported from the New World.

Interestingly, mercury is spirilostatic, if not spirilocidal, to treponema pallidum. Thus, it may inhibit the infective organism to some extent, giving the body’s immune system some chance to expel it. Mercury though would never have been a cure for advanced disease.

Bismuth was introduced in 1884 as an alternative to mercury for treatment of syphilis, although its use wasn’t extensive, some say because it did not cause as much salivation and therefore clearly wasn’t working!! In 1908 Paul Erilich won the Nobel Prize for his invention of Salvarsen to treat syphilis (it is based on arsenic) and finally a true cure was introduced in the 1940s with penicillin.

The blue pill was given for other conditions as well as syphilis. It was used as a liver stimulant and was a good laxative. Famously the Royal Navy surgeons mixed it with senna to produce the Black Draught, an explosive cure for the constipation brought about by the low fibre diet of long 18th Century sea voyages. Sir Henry Thompson suggested blue pills for patients suffering from uric acid stones, in particular those prone to a poor diet with excess meat and poor in vegetables, to clear them out! Thompson was very interested in diet and recognised that a high meat diet predisposed to urate stone, which were the commonest stone type in the 19th Century.

It is not clear how blue the blue pill was. Some authors have suggested a dye was used to make it blue but there is no evidence of that in 19th Century recipes and there is no real reason for the pill to be blue. Mercury chloride is brilliant white, but becomes grey over time or if not pure; maybe it gave the medicine a blue hue when mixed with the other ingredients.

Let us return to the more well known blue pill, in our age at least, Viagra. During the 1980s in Sandwich, Kent, the scientists of the drug company Pfizer were working on a new medicine for heart disease. The drug, UK-92480, synthesised in 1989, was found to dilate blood vessels and so it was felt may be useful for the treatment of angina. By 1991, UK-92480 was being given to patients as part of a clinical trial. Researchers and indeed patients became aware of an unusual side-effect; it appeared to improve these cardiac patients’ erections. UK-92480 certainly dilated blood vessels, just not so much in the place expected.

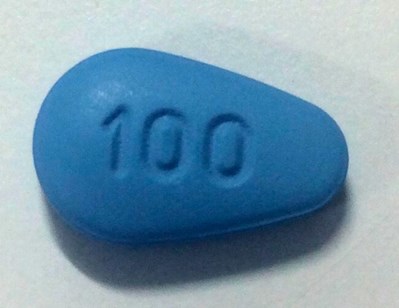

UK-92480 is sildenafil citrate and was marketed as Viagra after being given US and European licences in 1998. It is a diamond shaped bright blue pill. The success of Viagra for Pfizer was record breaking; over $1 billion worth were sold in its first year. Pfizer’s medicines patent for Viagra has now expired and generic sildenafil is available and can be bought off prescription from pharmacies – it’s still blue however (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A 100mg tablet of sildenafil citrate.

With thanks to the Pharmacy Department of Leicester General Hospital.

Both blue pills had a certain mystique about them. Syphilis and erectile dysfunction, both associated with sex, are embarrassing conditions to discuss. However, over time, and in their own way, both became more open to discussion. The use and popularity of Viagra has made it easier for patients to present with and talk about erectile and indeed all sexual problems. In 18th Century London Society, gentlemen who had not had a course of mercury for syphilis were seen as clearly somewhat provincial, and not real men about town. Unfortunately, the two-year course of mercury recommended by the doctors to clear the disease before marriage did not work and many young rakes passed on the disease to their new wives and then by vertical spread, to their children. Sadly, the signs of primary and secondary syphilis can resolve spontaneously, allowing the patients and their doctors to believe the blue pill had worked.

Figure 3: Medicine bottle for Pil. hydrarg. Subchlor. or mercury pills, dated 1937.

Both mercury and Viagra began as medicines to treat other diseases becoming famous (or infamous) for very specific conditions. The blue mercury pill was a very popular remedy and was still in use (particularly in patients who were unable to take Salvarsan) until after the Second World War (Figure 3). Viagra was, commercially, one of the most successful medicines of all time and it’s a lovely colour!